Summer 1972: It felt right to settle into the catching position, as though that was where the baseball diamond wanted me.

More than a year before, of necessity, I was called upon to catch while playing a college baseball game. Having never before done this, as I pulled on the gear my curiosity was mixed with uncertainty; the overflow from a considerable anxiety of the unknown. How would I react when a swung bat was in the same vicinity as the moving ball, my hand, and my head? Would I close my eyes? Worse, would I flinch?

I crouched behind the plate and the first pitch was delivered. The batter swung and missed. My eyes didn’t close. I was playing pitch and catch with the pitcher, and the fact of a batter swinging a bat near my head and hand was inconsequential to me. Whew.

Now I was on a single-A farm club in San Diego’s organization, playing in the Pacific Northwest League, and another opportunity arose to catch. This was my chance. This felt right. My hitting was fair, and I was determined to learn this new position that seemed to be my best route to advancement, and it was fun.

The first step of a little boy’s dream was being realized; I was getting paid to play baseball.

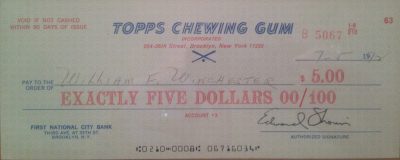

The day the Topps Chewing Gum representative came by to secure each player’s agreement to perhaps one day have his photo on a baseball card was sufficient to reinforce the thought that my larger childhood dream might be within reach. The Topps compensation for attaining the majors and having a baseball card with your photo on it was $500 or a new set of golf clubs.

It was 5 July, 1972.

Don’t believe me? Take a look, because I never cashed my check.

Have sometimes wondered if I jinxed myself by never cashing that check, because exactly one month later. . .

We were practicing first and third scenarios; a defensive exercise whereby runners on first and third were instructed to simulate baserunning strategies we might encounter during game conditions. There were several defensive reactions to be practiced, including infielders moving to various spots as the runners broke, and the catcher, me, throwing to different infielders, or the pitcher. An historical note about the frequency of this exercise is that baseball teams have been practicing this since day one of the modern baseball era.

I was learning a new craft, and making progress. My hitting was improving, but right now it was very important for me to develop skills, understanding, and field management for the myriad of scenarios which could arise.

People, even long time fans, may not fully appreciate that baseball is a mental game involving practice and more practice for responding to this and that imagined scenario, and when you think you’ve got it mastered you go back and practice it again and again so that you respond instinctively to game condition permutations. They become second nature. Then one day a play develops that you never, ever, dreamed could possibly occur, and on that day the immaculate Derek Jeter makes one of the great defensive plays of all time; by being in a place no shortstop has ever been, fielding an errant throw from a rightfielder that misses the cut-off man, while Jeter is standing at an impossible angle to properly throw the ball. . . then making a perfect backhand flip to nab the Oakland Athletics’ Jason Giambi at the plate to protect a 1-0 Yankees lead. In the history of baseball that play has probably never been practiced; but what Jeter did in that moment was the sum of countless hours of anticipating what might happen and making an instantaneous response.

So ‘first and thirds’ as we called it were nothing new. My arm was warm and the day was bright. Everyone was ready and so we began. I had a strong and accurate arm, to the extent that seventy-five percent of my throws to second base were right on your glove, and I was working to quicken my ball release. When guys wanted extra batting practice they would ask me to throw to them because I could throw strikes all day.

First up was a scenario whereby the pitcher would throw the ball to me at the plate and the baserunners would break as instructed. I would then fire the ball to the shortstop as he charged hard toward the plate, and we would go from there. Easy.

I caught the first ball and threw, and our shortstop had to reach to catch the ball. His having to reach threw off the defensive timing of the play and both runners were safe. No big deal. Do it again. No problem. Repeat and drive on.

My second throw forced the shortstop to jump to catch the ball, and once again the defensive play blew up. Hmm? What is this? Do it again.

My third throw was retrieved from the base of the 375 foot sign in left-center field. Our assistant manager, who was standing near shortstop, looked at me and yelled “What the f**k is wrong with you?” . . . “Something’s not working right and I don’t know what it is”.

I didn’t know what it was, but of one thing I was certain; what had been before no longer existed. Throwing unconsciously to an intended target had vanished. The ball in my hand attached to my arm being guided by my brain was no longer a seamless operating system. They were now separate mechanical and mental parts who were barely communicating with one another. I had no idea how to fix that which I had no idea how it worked in the first place. It, throwing, had always just happened.

The next night we played Lewiston, Idaho, and their first batter, a lefthander, struck out on a curve ball that hit the dirt. I scooped the ball cleanly and took a step left inside the first base line as I’d done many times before, to afford a clear throwing path to first base. . . drew back my arm and . . . threw the ball into the grass about ten feet in front of my shoes.

I had the yips. It was indescribably embarrassing.

And I knew in that moment that this dream had ended.

It was replaced by a better reality than I could have imagined.